When I ask the question, "why can't computer vision see the past?" the narrow answer is because computer vision is linear algebra, and as an art historian I reject the premise that math is sight.

But the big answer is that the data extraction and brokerage industry is leveraging computer vision and a host of algorithmic models to erase the incalculable parts of history to engineer a profoundly anti-human future.

These lines above are the concluding sentences to a talk I’ve been giving all around my region this fall. (Here’s a great write-up by student journalist Rohina Mahadik.) They encapsulate the conviction I have that understanding what the AI industry is doing to education isn’t, at core, about education; it is an assault on the structure of civic society, and educational institutions are just one of the pillars that are being knocked down to dismantle the whole edifice.

***.

Yesterday I visited Sing a New Song: The Psalms in Medieval Art and Life, an exhibition of Psalters—one of the most consistently produced types of manuscript during the Middle Ages, which contains the text of all 150 Psalms. This was arguably the most successful exhibition of medieval art I’ve ever attended: the thematic organization of the galleries, the discursive wall texts and object labels, the sub-themes in each vitrine, the blockbuster objects shown…perfection. But this isn’t a review. This is an opportunity to talk about the value of human memory and of embodied perception.

One of the things that I value about exhibitions is that they offer me a chance to exercise my eyes. As a professional art historian I believe that it’s fundamental to our discipline to be able to have a well-trained sensibility for form not so that we can make judgments about quality but so that we have a robust mental stock of images and objects that we use to assist us in contextualizing any object we might be researching. When I visit an exhibition I first look at the work and register my initial impression: when and where do I think it was made? What can I identify in the image, what perplexes me, etc? I then turn to the label, check to see if I was right, in the ballpark, or wrong, and then I revisit the work to see what it was that led me astray and what are the features that are more “right” to the period and place when and where the work was produced. Then I store the work in the correct spot in my memory for the next time I see something similar. It’s easy to see how someone who doesn’t practice this regularly might compare it all to the way that computer vision works. It’s tempting to refer to the repository of works of art and architecture in my brain as a “database.” But it is none of that because my memories derive from physical experience and my manner of accessing them does too. Objects are not pixels or weighted numerical values attached to them; neither is my recollection of them. Anyway, so that’s all the preliminary stuff I do before I really begin thinking about the works on display, their place in the exhibition, and the story they’re being used by the curators to tell.

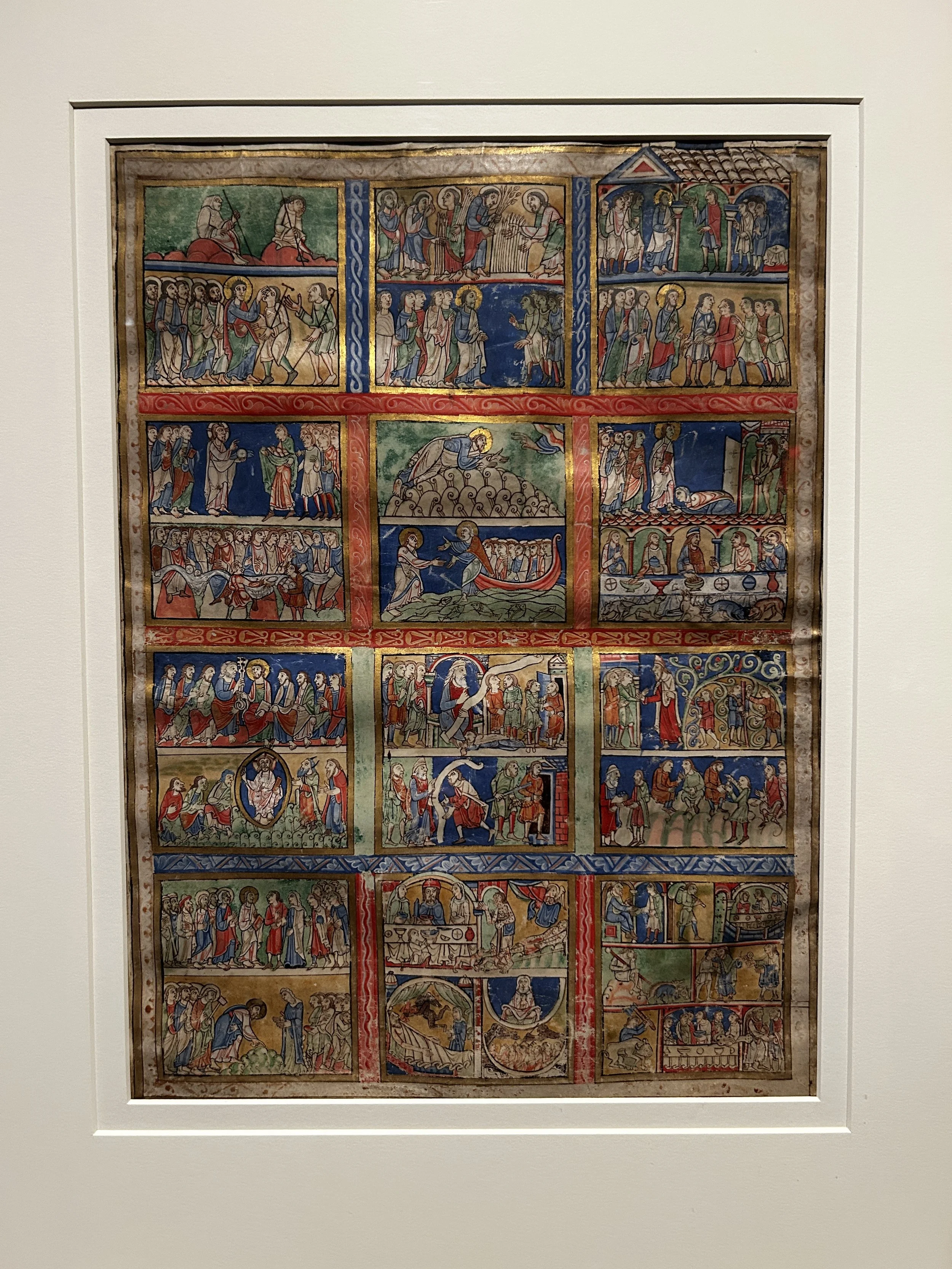

So I’m at the Morgan, and I’m eye-drunk on the splendor. But I get to this leaf, and it stops me in my tracks.

I’d never seen it in person before.

This is a leaf that was once dismembered from the famous Eadwine Psalter (aka the Canterbury Psalter). And I know this, but still. I do the thing. Because I’ve never before experienced it as a thing-in-the-world, as opposed to a reproduction, and I want to pop this badboy into my peepers. So I approach it, and for a moment I’m perplexed. This is, no-question, mid-12th-century England; this is the Eadwine Psalter. I’m not going to bother enumerating the minutiae, Morelli- or Berenson-style to say why I know it. I just do after having spent 25 years studying manuscripts from medieval England. Here’s another leaf that the Morgan has, which was also dismembered from this manuscript, but this is a scan of it, which, as you can see, flattens and deadens it. So I see it, and I know what it is, but there is something off about it. It doesn’t feel “right.” Now we know that the illuminators who made this manuscript were looking back at earlier models. The Eadwine Psalter is famous for that. One thing they were probably looking back at is this, the St. Augustine Gospels, a gospel book that was possibly brought from Italy to Canterbury in 596/7 (but certainly some time in the 7th century as part of the Roman mission to to the British Isles), and it remains just 100 miles away in Cambridge to this day. It’s fucking awesome.

The unusual gridded format might clue you into the fact that the 12th-century artist is looking to earlier books. But what defies enumeration, what emanates from the leaf as you perceive it with your own eyes and body is how purposefully archaizing it is. Yes, the artist is working in a 12th-century idiom with 12-century pigments, but he was also attempting to capture something of the older style, the forms from half a millennium prior. He was painting retro.

None of this makes for the kind of empirically authoritative work that gets valued in the academy. To a non-art-historian it probably sounds like I’m vibing. I get it. I know. And if I could program an algorithm to detect the degree of purposeful archaism in a work of art, I’d get grant money and esteem. But I cannot. There is no way to calculate how someone from the past saw the past. But to the extent that I’m an expert who has been researching this particular past for more than half my life, you’re going to have to trust me.

And ultimately, as I have said elsewhere, we cannot function as a society without trust, certainly not without trust in expertise. Especially when it comes to images.