In 1946, Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares published a short story called “Del Rigor en la Ciencia” (“On Exactitude in Science”) The story, which you can read in the original magazine context in which it was published on page 53 here, goes as follows

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

(Suarez Miranda,Viajes devarones prudentes, Libro IV,Cap. XLV, Lerida, 1658)*

This short story is gold for any educator who wants to get across to students the idea that maps are representations and that to think that a map is in any way an objective projection of the territory that it represents is pure folly. To attempt for such “obectivity” would require a duplication of the territory itself, rendering the map useless. Or, as we in art history teach our students day-in-day-out: a representation of a thing is not the thing.

Recently, historians have once again had to remind a new phalanx of tech enthusiasts that, no, not all of the world’s knowledge (which they always seem to equate with written things and not other kinds of artifacts, but that’s another battle) has been digitized.

There’s a wonderful piece from 2019 by Marc Reyes in Contingent Magazine that not only explains this fact but also addresses why physically going to libraries, archives, and rare books collections is important to the research process. I was reminded of this essay by a Bluesky thread by Erin Bartram, historian and editor of Contingent Magazine, which fleshes out some of its discussion. If you haven’t read either, click the links and do so.

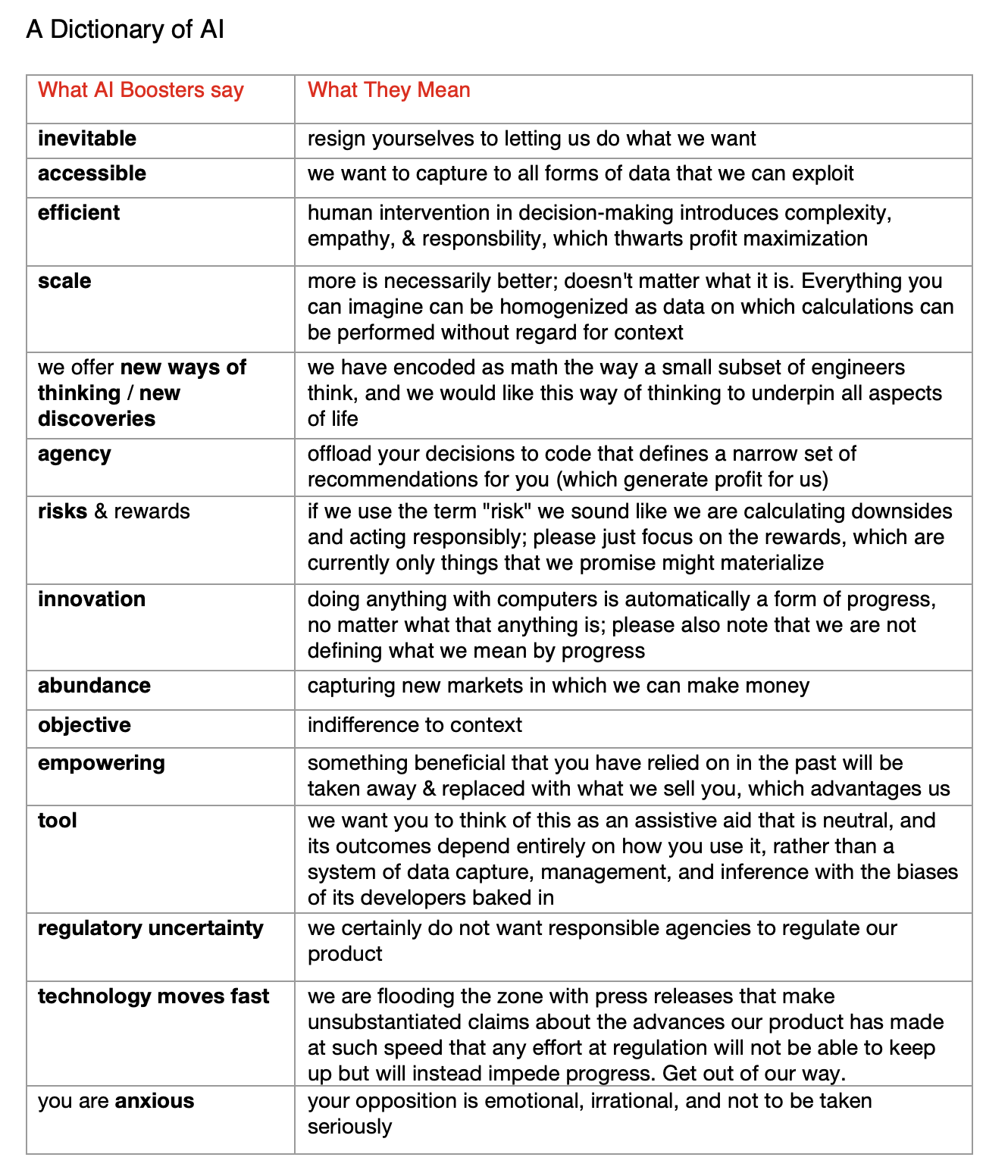

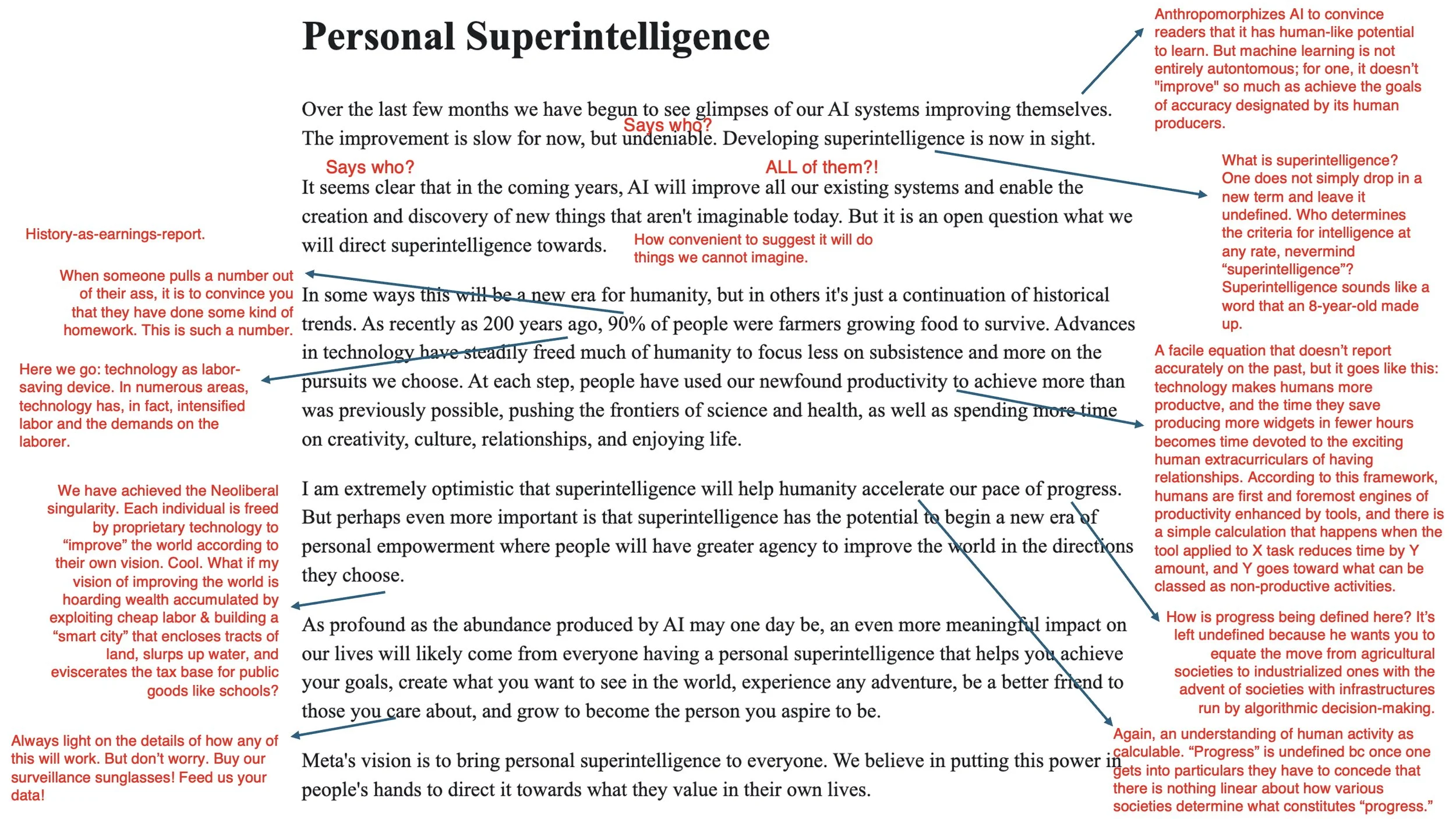

These discussions might tempt the casual reader, and maybe even some historians, to think that the “solution” (there is no problem here, or if there is, the problem isn’t digitization; the problem is the underemployment of archivists and librarians and curators…it’s always a labor problem), but anyway, the “solution” that might occur to some people is to renew digitization campaigns so that AI can then be unleashed on these newly digitized materials, and we can OCR our way towards Complete Knowledge of Everything. Certainly this is what OpenAI is promising in their new partnerships with libraries and archives from Howard University to the Bodleian Library.

There is an end-game here, an end game that entails an arms race to hoover up more data for ever more model refinement, so I would argue that partnering with OpenAI is a devil’s bargain. But let’s leave that aside for the purposes of this post.

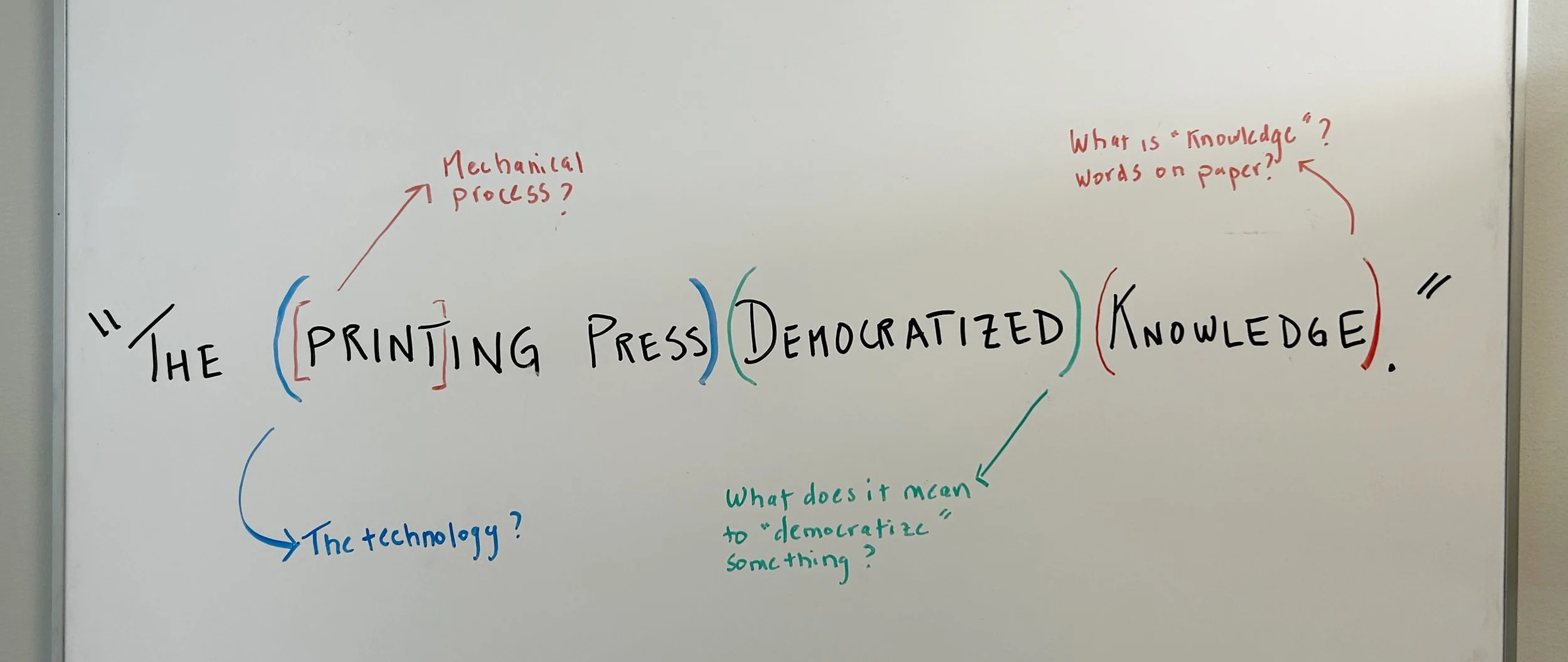

If you go back to Marc Reyes’s essay, to Erin Bartram’s Bluesky post, and to all of the many, many quote posts and responses, what you’ll find is something far more systemic impeding the utility of “just digitizing” (it’s never a matter of just when it comes to digitizing, for which read Bridget Whearty’s excellent Digital Codicology on that kind of labor). And that something is this:

the sheer recalcitrance of diverse materials to the homogenizing process required both by digitization and processing by means of AI.

None of the materials that we are talking about here are born-digital objects. Our archives comprise rag paper, birchbark, nose grease on parchment, worm holes, water stains, creases and pleats, linen curtains, sixteenth-century secretary where every letter ‘h’ took a left turn at the corner of drunk and dizzy; they are everything idiosyncratic whose essence is resistant to the need for flattening that AI products demand.

It is not simply that you cannot CTRL-F the archives for a doctoral dissertation; it’s that CTRL-F-ing would only grasp in a partial and deeply impoverished way the bare lexical content of things in the world that we can only see as such when expert librarians, archivists, curators, cataloguers, and historians have deployed their expertise in making them visible. This is necessarily an inefficient process—it is the WORK OF HISTORY. And in doing it, we adduce more information, more context, more knowledge to the artifacts. Digitization is just one part of it.

None of what I have gestured to is the work of duplication that any program of digitization and automated processing could achieve. If it did, all we would have would be a second earth of digitized objects and data centers littering the wasted landscape they reiterated. And no one would be wiser for it. We would, in fact, be smothered to death by the ecocide.

The digitization is not the archive.

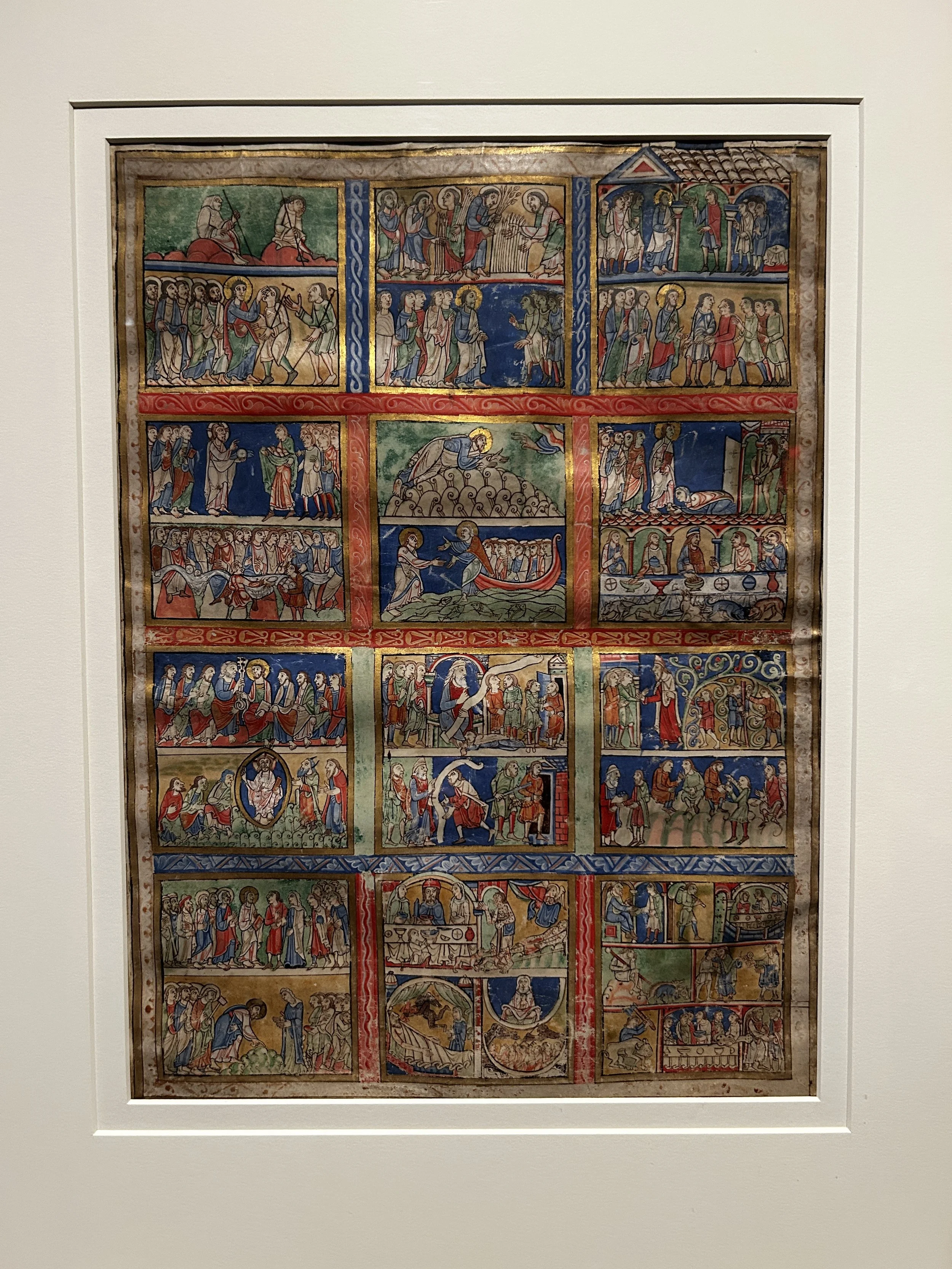

Here’s a screenshot of a manuscript on which I published many years ago. It contains a damaged fifteenth-century leaf , and underneath it you see the image that Eliza Dennis Denyer (d.1824) restored to it. Next to it is the nonsense of what OCR made of the page.

*translation of “Del Rigor en la Ciencia” here